As a Louisville native, I am honored to be a part of the city in Kentucky that holds the most ties to black history. From housing laws to education, Louisville illustrates a history that defines the advancement of African-American students and families. It’s interesting to know that the State of Kentucky had no intention in supplying higher education for African-American students, yet various communities felt otherwise. I did some research and found information that lead to higher education. In 1874, a separate state system of commons schools was created by the Kentucky General Assembly and in 1891, Kentucky legalized segregated public education. It wasn’t until 1920 that community members faced challenges of being associated with the University of Louisville.

The city of Louisville had a municipal bond issue related to not giving African-American students the opportunity to attend an institution. Two-thirds affirmative vote was required in order to pass this bond. It was evident that Louisville officials within the city and of the predominately white institution did not consider discussing efforts with African-American leaders. At this time, segregation in the American society was unchanging. Outraged, people fought for equality and stressed that taxes from the African-American community should not be used to fund the higher education of only whites. They wanted an institution that reflected their desire in developing collectively and individually working towards a brighter future. The bond was unsuccessful and demonstrated the power of the black vote. By 1925, a new bond was passed and the University of Louisville promised to establish an institution solely for African-Americans.

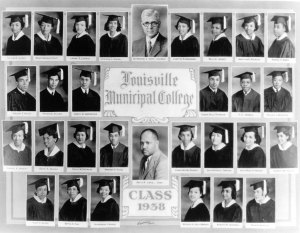

In February of 1931, the Louisville Municipal College for Negroes (LMC) was founded and opened to students of color who sought to be great. It served as a separate higher education institution set on the principles of black pride and excellence. The University of Louisville’s Board of Trustees administered the separate institution seeing as it was a purchase made to ensure their promise. Imagine sitting in a classroom with students just like yourself. Colored students with common career goals and hopes of graduating. Back then, it was empowering to know an institution was granted to African-American students towards bettering themselves and earning a degree that would be extremely beneficial. From 1931 to 1951, the LMC offered a four-year liberal arts curriculum and progressed in providing a prestigious library, a student center, sororities and fraternities, and a campus newspaper. The establishment was successful in graduating more than 500 African-American students.

The LMC closed in 1951 and the University of Louisville chose to desegregate their Belknap campus along with their professional and graduate schools. Though this decision was made, segregation continued through everyday experiences of attending class and becoming a part of the University’s community. Every generation attending the University of Louisville had their wave of African-American students attempting to create a positive status once enrolled. From on-campus marches against the acts of the administration to establishing links between politics and social justice, African-American students found ways to be involved and make the importance of their education known.

Paying homage to the late Dr. J. Blaine Hudson, we remember the efforts made by him to unite African-American students as they enrolled into the University of Louisville. He developed the Black Student Union in 1968, an on-campus organization influenced by the nationally known Panther Party and the Black Power Movement. Hudson defines a movement as such: “…a movement is more like a loosely defined network that it is a big formal organization with dues and by-laws and a building…”. He did just that in the networking of trying to begin the Black Student Union on other universities and even in local high schools. The Black Student Union shared with the public a newsletter and a tutoring program for West End centers. Hudson shares: “ …You’ve go to do more than talk about the ways in which a society should be changed, you’ve got to get involved in changing it.” The founding of this organization and many others on the University of Louisville’s campus illustrates the history behind change.

The Late Dr. J. Blaine Hudson

Today, the Louisville Municipal College for Negroes is remembered as the starting point for colored Louisville natives with a passion for learning and advancing in life. The University of Louisville has become more diverse then ever before. I am proud of be a Louisville Cardinal. I am proud to represent the heritage that my people have fought to show. To know that those before me cared enough to shape my future as well, motivates me entirely. Even though we still struggle to tackle cultural barriers, we progress in taking steps towards unity.